The signs were there. And they were ominous.

On November 16, 1963, Ron Robinson was covering the Razorbacks in Dallas as they played the SMU Mustangs for Arkansas’ student newspaper. In the area around the Cotton Bowl, where the game was played, the 20-year-old noticed billboards that had been paid for by the John Birch Society, the same extremist group which was then distributing pamphlets picturing President John F. Kennedy above the words, “Wanted for Treason.” He also noticed people on street corners in downtown Dallas passing out small fake dollar bills featuring Kennedy’s profile. The idea was to show “this was the shrunken dollar as a result of JFK’s economic policies.”

“Looking back on it, there was an anti-Kennedy feeling in the air,” he recalled. What Robinson had seen was only the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, Dallas was becoming a very dangerous place for the president who was scheduled to arrive the following Friday.

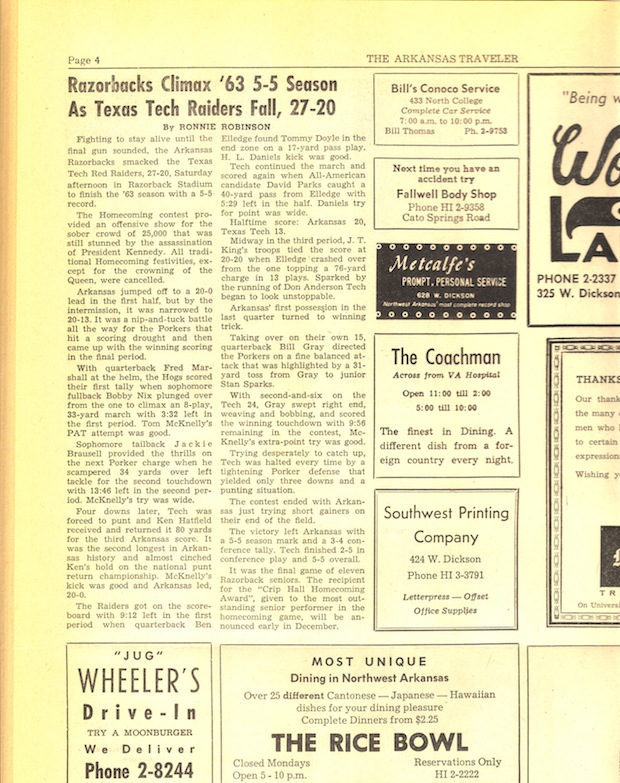

On the field, Arkansas lost to SMU 14-7, dropping to 4-5 overall (2-4 in conference) and further continuing an extremely disappointing season. Heading into the fall of 1963, the Hogs had the most talented team in program history and were preseason Southwest Conference favorites. At the end of the previous four seasons, Arkansas had finished in the Top 10 of the Associated Press poll. In 1960-62, the team had captured the SWC title or finished within a half game of it.

Head coach Frank Broyles was distraught after the SMU loss, he recalled in his autobiography Hog Wild. “On the way home, I was sitting on the plane as low as I could be when I looked up and saw six or seven of the seniors-to-be coming toward me: Jerry Lamb, Ronnie Caveness, Fred Marshall….” He recalled them saying: “Coach, we’re so disappointed in ourselves that we just don’t know anything to tell you except that you’re gonna to see a new football team. Monday we want to go out and scrimmage. We want to win this last game, and next year we’re going to be a great football team.”

The players went on “about how they had let themselves down, how they thought they were going to win by just walking out on the field, and they hadn’t worked like they should.”

Broyles liked what he heard, and he was willing to switch it up for the sake of finishing strong in Arkansas’ homecoming game: “Ordinarily we had little contact work during the season and never on Monday, but we went out the next week and put on the pads Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and got after it like we were back in two-a-days.” Things looked promising for the season-ending game against Texas Tech, which had a record of 4-5 overall and 2-4 in conference.

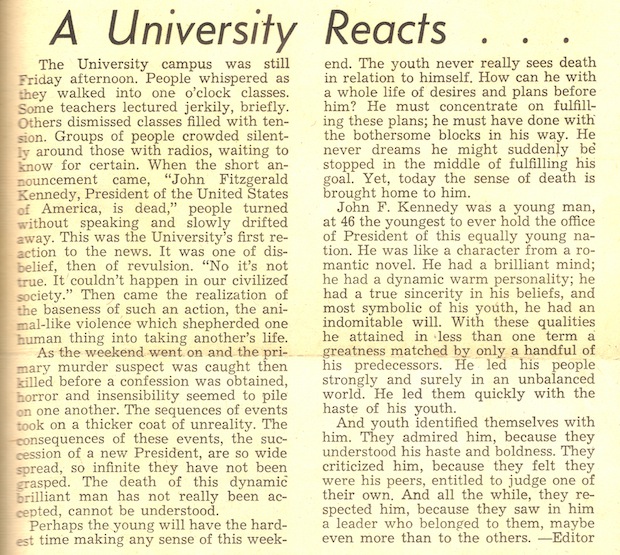

The tenor changed that Friday, November 22, soon after 12:30 p.m. The Razorback coaches including Broyles were playing Moon, a kind of card game with dominoes, in an athletic dorm game room when Martine Bercher, a future All-American safety, walked in and told them that the president had just been shot, recalled Barry Switzer, then a third-year assistant coach. Everybody was shocked. Lunch plans were forgotten as all rushed to a larger room downstairs where there was a TV. “There was dead silence,” Switzer recalled in an interview for the Wall Street Journal. “We missed the meal because we all sat there glued to the television.”

As the news broke that Kennedy was dead, and Lyndon Johnson had taken over the presidency, the team went on with business as usual. “We were all obviously shocked and saddened by the event but we had to focus,” Switzer said. “It didn’t affect how we played or prepared or how we went about the game.” Former Razorback Ken Hatfield added: “As a player, on Friday afternoon, you went to your meetings. You did what you had to do. You went to your hotel and we had to just wait and see if the game was cancelled.”

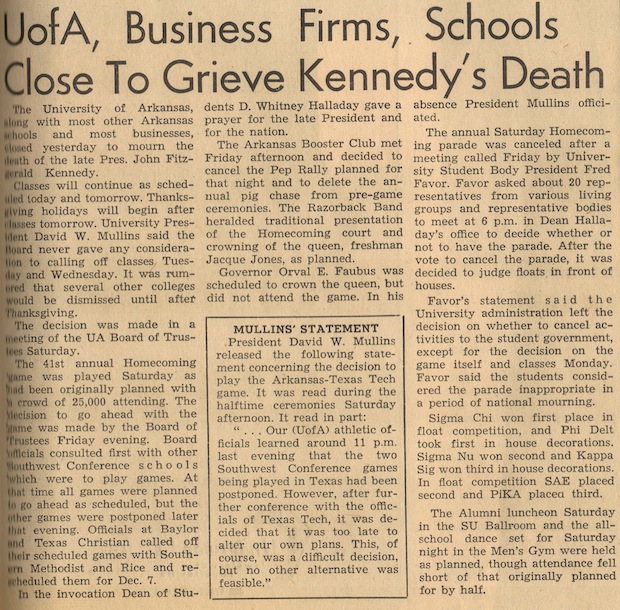

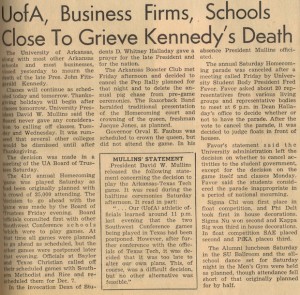

University of Arkansas officials were conferring with other SWC programs throughout the day and at first heard Baylor, TCU, SMU and Rice would play their games as originally scheduled. They didn’t learn those programs decided to instead postpone their games until 11 p.m. This, combined with the fact Texas Tech was already in Fayetteville and that it was homecoming, led to a decision that “it was too late to alter our own plans,” President David W. Mullins said in a statement released at halftime of the following day’s game. “This, of course, was a difficult decision, but no other alternative was feasible.”

University of Arkansas officials were conferring with other SWC programs throughout the day and at first heard Baylor, TCU, SMU and Rice would play their games as originally scheduled. They didn’t learn those programs decided to instead postpone their games until 11 p.m. This, combined with the fact Texas Tech was already in Fayetteville and that it was homecoming, led to a decision that “it was too late to alter our own plans,” President David W. Mullins said in a statement released at halftime of the following day’s game. “This, of course, was a difficult decision, but no other alternative was feasible.”

Arkansas and Texas Tech ended up being the only SWC game to be played that day. Two other Southwest Conference games scheduled for Saturday, November 23, were postponed to December 7. Arkansas State’s game at San Antonio’s Trinity University was cancelled. Texas played Texas A & M on November 28, on Thanksgiving Day, as scheduled. The undefeated Longhorns beat the Aggies 15-13 to secure that program’s first consensus national title.

While Arkansas players and coaches bunkered down on the afternoon of November 22, there was much activity elsewhere on campus. Right after the announcement of Kennedy’s shooting, Arkansas’ leaders voted whether their athletic programs should break the color line. At a meeting, the University of Arkansas Board of Trustees reaffirmed the school’s policy of keeping its athletic department closed to African-Americans. Arkansas, like every other SEC and SWC team of this time, was all-white, but in November 1963 the ground was being tilled for change. On Nov. 9, 1963, Texas became the first SWC program to announce it would integrate its sports. Southern Methodist University followed suit in the coming weeks and Baylor’s Athletic Council voted for integration with a unanimous vote on Nov. 23. In response to these developments, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus stated at a news conference he would “oppose the use of Negroes on Arkansas teams,” according to a Nov. 23, 1963 Arkansas Gazette article. In reports, Broyles deferred to administrators, saying it was their decision and not his.

The Gazette’s sports columnist, Orville Henry, said Faubus’ stance in reality made the UA trustees’ opinions a moot point:

“From a practical standpoint, Arkansas fans need not fear, cheer, or expect (whatever their inclination) the arrival of an integrated Razorback football team for from three to five years.

If anyone needed a cue, Gov. Faubus supplied the only one necessary. This is not a matter of dealing with a locally-controlled school board. This is something which lies within the realm of his political appointees and he can expect their loyalty, as they can respect his political shrewdness.

SO that’s that.” [sic]

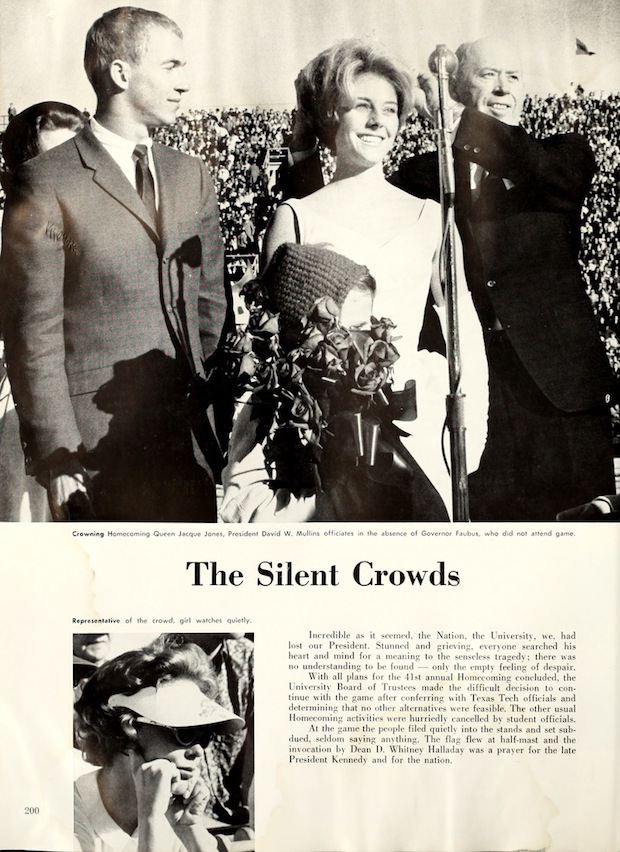

From Friday afternoon through the game’s kickoff on Saturday afternoon, there was much debate among students regarding whether it was appropriate Arkansas should play. Many students felt like it was inappropriate, recalled Ron Robinson, the Arkansas Traveler editor. “There was nobody who wanted the game to be played. It was an absolute period of national mourning and that’s all people could think about. They were upset, they were crying, they were attending church services … We’re talking about an entire nation draped in black.”

appropriate Arkansas should play. Many students felt like it was inappropriate, recalled Ron Robinson, the Arkansas Traveler editor. “There was nobody who wanted the game to be played. It was an absolute period of national mourning and that’s all people could think about. They were upset, they were crying, they were attending church services … We’re talking about an entire nation draped in black.”

“I was terribly saddened and affected by the Kennedy assassination and felt like our nation’s interest were much more important than a football team’s athletic contest,” Robinson added. “JFK was a very popular man among college students. He did much to encourage some people, with the development of the Peace Corps and support of education.”

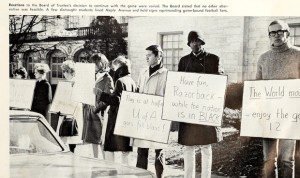

Robinson was supposed to be a judge for a Greek decorations contest in the upcoming Homecoming festivities, but he called the organizers and said he felt like the contest should be cancelled. Indeed, all traditional homecoming festivities ended up being cancelled except for the crowning of the Queen. On Saturday, about 10-15 students held a protest near the corner of Maple Avenue and Dickson Street, where the Homecoming parade would have started, Robinson recalled. They held signs voicing their displeasure with the administration’s decision to play the game.

Arkansas players Fred Marshall and Ken Hatfield don’t recall any protests on campus but Razorback Jim Lindsey knew about the signs, he said in the the documentary “22 Straight: Razorback Football.” He said the campus climate couldn’t help but affect the team’s spirit a little. “It wasn’t the highly motivated game that it seemed.” The somber atmosphere, as well as an incoming cold front and heavy rain throughout the state that Friday, had many thinking the turnout for the game could fall to as low as 15,000 people.

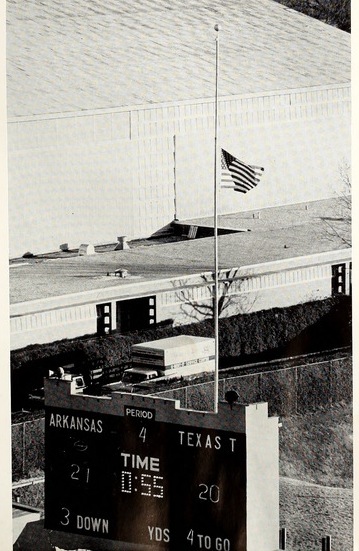

So, when 25,000 people showed up, it was a surprise, Arkansas Gazette columnist Orville Henry wrote.

Arkansas jumped to a 20-0 lead in the first half, with the help of Ken Hatfield’s 80 yard punt return for a touchdown – the longest ever for a Razorback in conference play to that point. Texas Tech closed the gap to 20-20 by the middle of the third quarter and it looked like Arkansas was about to suffer a breakdown of circa 2013 Rutgersian proportions. But quarterback Bill Gray helped lead an 85-yard drive early in the fourth quarter, capping it with a 24-yard touchdown run with 9:56 left. Arkansas defense tightened, holding Tech to only three yards the rest of the game.

After the game, Broyles praised specific Texas Tech players like Donnie Anderson, Jim Zanios and David Parks but he refused to give credit to specific Arkansas players. “I’m so proud of everyone today that I don’t to single anyone out,” he said to the Gazette. Still, he’d seen a lot of good plays from the likes of Hatfield, quarterback Fred Marshall, quarterback/cornerback Bill Gray and linebacker Ronnie Caveness. An even more talented team would return the following year, and based on what he’d seen in the last week on the practice field, they would also be the most mentally prepared team he’d ever had.

After the Texas Tech, the Razorbacks did not lose again until January 1, 1966. Twenty-two straight wins and a national championship showed a new dynasty had emerged.

On the Razorbacks’ field that downcast Saturday afternoon, Broyles had seen signs. And they were promising.

Newspaper photos are courtesy of the University of Arkansas Special Collections

***

Evin Demirel writes often about Arkansas sports and society. Follow him on Twitter or through his blog.