10 Years Ago This Week Arkansas Razorback Football Star Fullback Mark Pierce Returned to Fayetteville a New Man

For at least 60 years, the word “beast” has been a good thing in the world of football. It was used in the 1950s as the nickname for Texas Tech’s All-American center E.J. Holub. These days, it signals praise for the Dallas Cowboys’ gifted young wide receiver Dez Bryant.

To earn the moniker, you’ve gotta be big and strong. You’ve gotta be tough. And you must be extraordinarily talented.

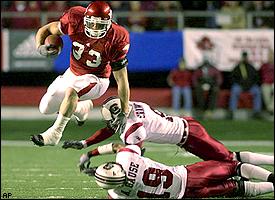

Few players in Razorback history have combined these traits like Mark Charles Pierce.

A 6 feet tall, 247-pounder who could run a 4.5 40-yard-dash, Pierce was a crucial cog in the Hogs’ SEC-leading run offenses of the early 2000s. He announced his arrival as a true freshman with three touchdowns against Ole Miss in 2001 and throughout his career scored roughly one touchdown for every eight times he touched the ball. He was an Arkansas Razorback football star.

He inhaled a 5,600-calorie-day-diet before his sophomore season so that he could better play with “the kind of barbaric zeal one expects from a human battering ram,” as the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette’s Scott Cain wrote in August 2002.

“I would love to play tailback but I love to smash heads, period,” Pierce said. “At fullback, I’m just killing linebackers. We do that Oklahoma drill, I like nothing more than to just run ’em over, just show ’em that we’re tough on offense. I’ve accepted that role.”

The top three rushers for whom Pierce blocked – Cedric Cobbs, Fred Talley and Matt Jones – have landed among the program’s Top 8 all-time career rushers. That likely doesn’t happen without Pierce, who entered his junior year as the Sporting News’ top fullback in the nation.

And Lord, could this guy suck it up.

When Pierce’s shoulder got knocked out of joint during games, he’d shove it back in place, return to the field to deliver more bone-rattling blocks,according to Wally Hall, the Democrat-Gazette’s sports columnist. He played an entire season with a dislocated shoulder, choosing to forgo surgery until the offseason. Pierce’s father died unexpectedly before the 2002 SEC championship game against Georgia. He took a magic marker, wrote “Dad, RIP” on his forearm, and played anyway.

But in the following months, Pierce couldn’t erase the pain no matter what he tried. Something had broken, and this time he couldn’t just pop it back into place. “I was really mad at the world after I lost my father,” Pierce told the Democrat-Gazette. “It came to a point where I slowed down hanging out with people on the team. I was hanging out just in the wrong places.”

In July 2003, he left workouts with his teammates and returned to his hometown of Weatherford, Texas. His goal was to spend time with his mom, who was recovering from surgery, and attend to what had the time were simply described as “emotional issues.” “He is dealing with some things,” former head coach Houston Nutt said. “It has been a very tough last six months.”

Nutt added: “I know that some things are heavily, heavily wrong and [they are] some things professionals need to deal with.” That professional help, it was later announced, came in the form of four weeks at a chemical dependency treatment center in San Antonio.

In mid August, Pierce returned to the team as a self-declared new man. He’d kept working out and had become bigger, stronger and faster than ever. Most importantly, he’d found Jesus. “I was trying to control everything with my own self will, and it really just took God to open up my mind and have a willingness to let Him come into my Heart,” he told the Democrat-Gazette.

Pierce marked his rebirth as a Christian through baptism in the Guadalupe River. “It just changed my perspective on life. I find myself happy, joyous and free instead of angry and mad all the time.”

Despite the feel-good narrative, thunder clouds were already forming.

Within a few days, Pierce had told some teammates “his newfound spiritual life didn’t mean he was going to quit drinking,” Hall wrote in a December 2, 2003 column.

On the night of August 30th, the trajectory of Pierce’s football career – and, ultimately, his life – changed forever. First, he beat up a man at a Fayetteville liquor store, according to police reports. A misdemeanor battery charge resulted. Then, a few hours later around 1 a.m., police arrested the 21-year-old Pierce after they said he became belligerent and cursed at them. The police had been patrolling for underage drinkers and had found Pierce’s friend with a beer at Club 414. They started questioning Pierce’s friend when Pierce intervened. He didn’t leave when ordered and was arrested on misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct and obstructing governmental operations.

On the night of August 30th, the trajectory of Pierce’s football career – and, ultimately, his life – changed forever. First, he beat up a man at a Fayetteville liquor store, according to police reports. A misdemeanor battery charge resulted. Then, a few hours later around 1 a.m., police arrested the 21-year-old Pierce after they said he became belligerent and cursed at them. The police had been patrolling for underage drinkers and had found Pierce’s friend with a beer at Club 414. They started questioning Pierce’s friend when Pierce intervened. He didn’t leave when ordered and was arrested on misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct and obstructing governmental operations.

The fallout from this episode lingered through the rest of the 2003 season. Nutt suspended Pierce for the season opener against Tulsa but allowed him to play in the following game – a victory at No. 6 Texas. Playing with a dislocated shoulder, Pierce wasn’t as effective in his junior season as he had been as a sophomore.

His college career came to an anticlimactic finish at the end of the regular season following a reported run-in with the Arkansas coaching staff and, apparently, another altercation at a bar. “Pierce’s anger has become almost legendary,” Hall wrote. “If he had won half as many fistfights as was rumored, Mike Tyson wouldn’t want to face him.”

Hall added Pierce’s anger resembled “roid” rage. No matter the reasons, it became clear over the course of the fall that Pierce was too beastly for his own good. He had the perfect body and on-field temperament for his sport. And his ability to play through pain was otherworldly. He’d learned how to harness his wild side for the good of a team, and he’d done this for years and years, but in the end there was too much wrong bubbling up for him to keep it all contained. The same brutal, blow-’em-up attitude that took Pierce to the brink of making millions in the NFL ultimately turned off scouts and spelled his downfall.

Houston Nutt had given him multiple chances but ran out of patience in late November, 2003. Pierce left the team. He would not play in the Independence Bowl against Missouri in Shreveport, La. Nutt hoped Pierce learned from his mistakes and “wished him nothing but the best,” Hall wrote.

****

The best hasn’t happened yet. Far from it.

Pierce declared for the NFL Draft but wasn’t one of the six Razorbacks selected in spring 2004. He joined tight ends Jason Peters and cornerback Lawrence Richardson as undrafted juniors.

In 2005, Pierce tried for the Dallas Desperadoes, a now defunct Arena Football League team. He was cut. In 2006, he was sentenced to eight years in prison for possessing 1.73 grams of methamphetamine. Pierce was out on probation in December, 2008 when he made a series of horrible decisions.

First, according to Fort Worth police, he likely stole his mother’s Chevrolet TrailBlazer. He drove it to Southern Oaks golf club in south Fort Worth and there played with his brother and an uncle. He had at least six beers and a shot of liquor before returning to the TrailBlazer. On the road, Pierce passed a few cars – then slammed into a van.

Pierce reportedly fled from the accident and was captured about an hour later. He refused to take a blood test. The driver of van, a father of three, died at the scene. “I don’t know what I was thinking,” Pierce said at a July, 2010 hearing before he was sentenced to an additional 15 years in prison. “It’s the most horrible thing in my life. You hear about these things happening but you don’t think they’ll ever happen to you. But it can happen to anyone.”

He added: “I am not a monster.”

Mark Pierce now spends his days in the Beto Unit, a maximum security prison in east Texas. It does not appear to be the kind of place that inspires great hope in our country’s criminal justice system.

“Beto is a rough unit with a lot of gang activity. I’m not going to sugarcoat it for you,” wrote one message board commenter giving advice to someone whose loved one was imprisoned there. “Just tell him to watch who he associates with, stay out of trouble, take as many classes as he can, work, pray and do whatever he can to get out of there. They never have enough [guards] working so [the prisoners] NEVER get to go out for rec.

“Lockdown generally lasts for a month at a time and they usually do 2 per year. They stay in their cells the whole time but they still allow visitation on the weekends and they still receive mail and can send mail out.”

Maybe Pierce defies the odds and makes it out of this place still wanting to be a better person. Maybe, finally, the want will be enough.

Let’s hope this man who made a name for himself by clearing paths for everybody around him at last finds his own way.

Follow Demirel here.