Larry Foley, a professor of journalism at the University of Arkansas, has earned quite a reputation through the years for his work on documentaries.

Larry Foley, a professor of journalism at the University of Arkansas, has earned quite a reputation through the years for his work on documentaries.

The accolades are deserved. The man knows how to tell a story.

I first met Larry when I was a young newspaper sportswriter and he was working at KATV, Channel 7, in Little Rock. Foley was a reporter, morning news anchor, assignment editor and producer for one of the top ABC affiliates in the country. He then spent nine years at the Arkansas Educational Television Network before returning to his alma mater in 1993 to teach, produce documentaries and build a program for students who hoped to have careers as television reporters and producers. In 1996, Foley founded the campus television station, UATV.

By October 2003, he had made such a name for himself that he was inducted into the Lemke Department of Journalism’s Hall of Honor, the highest award bestowed on journalism graduates of the University of Arkansas. In October 2010, Foley received an award from the Arkansas Alumni Association for being the school’s outstanding faculty researcher. A year later, he received the Individual Artist Governor’s Award from the Arkansas Arts Council.

Foley’s productions have earned five Emmys from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. They’ve earned 13 Emmy nominations in community service, writing, journalistic enterprise, special programs, cultural history and history. His University of Arkansas students have been awarded an additional six Emmys for films produced under his direction.

Foley’s documentary credits include “22 Straight” on the Razorback football teams of 1964-65, “The Governor from Greasy Creek” on Orval Faubus and “The Buffalo Flows,” a film on the Buffalo River that ran on PBS affiliates across the country.

I’m biased because I love baseball and I love Hot Springs, but I think Larry Foley is about to embark on the project that will draw more national attention than anything he has ever done.

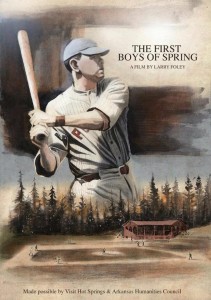

A group gathered at the Hot Springs Convention Center on a rainy Thursday morning for the official announcement that Foley will produce “The First Boys of Spring,” which will tell the story of how Hot Springs was the birthplace of baseball spring training. The Arkansas Humanities Council and Visit Hot Springs, the city’s convention and visitors’ bureau, have joined forces with Foley to make the one-hour documentary a reality. Foley hopes to debut the film at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival in October 2015. I predict it will be a hit not only at documentary film festivals but also on PBS stations.

“We’re extremely lucky that Larry Foley, whose documentary film expertise is nationally known, took interest in our rich baseball history and got in touch with us about the possibility of creating a documentary about the boys of spring,” said Steve Arrison, who heads Visit Hot Springs. “We’re doubly fortunate that the Arkansas Humanities Council saw the potential value of Larry’s idea for a film and generously gave us financial support. With input from our five baseball historians, Larry has already begun filming scenes.”

Those historians are Bill Jenkinson from Pennsylvania, Tim Reid from Florida, Don Duren from Texas and Mike Dugan and Mark Blaeuer of Hot Springs. Dugan and Blaeuer were present for Thursday’s announcement.

Media attention in the past month – since the late February fire that destroyed the oldest part of the Majestic Hotel – has been focused on what Hot Springs has done wrong. Among the things Hot Springs has done right is the establishment of the Hot Springs Historical Baseball Trail, a series of 28 historical markers around town. The trail was launched two years ago. It utilizes digital technology so visitors can listen to baseball stories at each stop.

“I’ve got a lot of kid in me, and that kid in me would like to play baseball if I still could,” said Foley, who was wearing a baseball cap for Thursday’s announcement.

He said he decided two years ago that this “is a film I really want to do. I think there is going to be incredible interest in this. This is going to bring people to Hot Springs. … Get ready for this project to make money for the city.”

Foley said that residents of Japan and Korea are “baseball crazy” and would vacation in Hot Springs if they knew the deep baseball roots in the city.

Dugan has a copy of a 1915 photograph of Red Sox and Pirates players and fans posing with Hot Springs businessman William G. Maurice, the man for whom the Maurice Bathhouse was named.

“It’s easy to see Honus Wagner, perhaps the greatest shortstop of all time, along with Bill Carrigan and Tris Speaker, another future Hall of Famer for the Red Sox,” Dugan says. “Now, if you look carefully in the back row, you can make out the head of a young Babe Ruth.”

Ruth fell in love with Hot Springs. He loved its gambling opportunities, its hot water, its mountains, its restaurants, its hotels, its bars and, yes, its women.

The Hot Springs Baseball Trail website tells the story this way:

“Early in his career, Ruth was the best left-handed pitcher in baseball. He was a combined 47-25 during the 1916-17 seasons. But Ruth was an even better hitter. He proved it with a long home run in a spring training game in 1918 against the Brooklyn Robins at Whittington Park. Ruth got to play first base that day. He responded with two home runs in two at bats, the second one a mammoth blast that landed across the street in the Arkansas Alligator Farm.

“The Red Sox traded Ruth to the New York Yankees in 1920. He continued visiting Hot Springs for a few weeks prior to joining the team’s spring training site. A big man, Ruth always seemed to be battling extra pounds packed on during the winter. He claimed the restoring waters at the bathhouses helped him do that. The Yankees began sending other veteran players to join him. But the undisciplined Ruth had a voracious appetite for food, alcohol and women. He partied continually and frequently left the Spa City in worse shape than when he arrived. Finally, after missing the first half of the 1925 season due to poor health, the Yankees forbade him to return to Hot Springs. A habitual gambler, Ruth continued to frequent the city after his retirement following the 1935 season. The story goes that in 1941, Ruth got involved in a high-stakes poker game in Hot Springs that was rigged. He lost all of his money. The Bambino felt cheated and never returned.”

Foley said he especially looks forward to telling the Ruth part of the story.

The Alligator Farm is still in business. Whittington Park is gone, replaced by a parking lot for a corporate office. But foundation slabs for the concrete bleachers can still be found. The first newspaper mention of Whittington Park was in 1894. The St. Louis Browns used the field in 1895 before moving their spring training camp to Little Rock due to a smallpox outbreak in Hot Springs. By 1909, the Red Sox and Pirates were training regularly in Hot Springs. The Red Sox stayed at the Majestic Hotel and built a second ballpark at the other end of the trolley line called Majestic Field. The Hot Springs Boys and Girls Club is now at the site.

The Detroit Tigers, Cleveland Indians and Washington Senators of the newly created American League later trained at Whittington Park. In 1912, Brooklyn joined the Philadelphia Phillies in building a new field on land behind the Alligator Farm. It was named Fogel Field in honor of Horace Fogel, the Phillies’ owner. The diamond is gone, but the field is still there. Dugan would like to see a wooden stadium constructed around it.

The St. Louis Cardinals and the Philadelphia Athletics joined the teams coming to Hot Springs. Players could be seen in the lobbies of the Majestic and the Arlington, in the bathhouses and walking down Central Avenue.

“They were accessible to the public,” Arrison said. “Though some, like Ruth, were larger than life, they enjoyed their celebrity status and didn’t shy away from their fans.”

Almost half of the Baseball Hall of Fame inductees were in Hot Springs at one time or another.

The list of people who spent time in Hot Springs includes Satchel Paige, Walter Johnson, Grover Cleveland Alexader, Rogers Hornsby, Carl Hubbell and Casey Stengel.

“The players liked coming to Hot Springs so much that in 1932, Ray Doan devised a plan to open a baseball school at the park on Whittington,” Dugan said.

The school opened in February 1933. Instructors at one time or another included Dizzy Dean, Paul Dean, Lynwood “Schoolboy” Rowe, Cy Young and Lon Warneke. Hornsby later bought the school from Doan and moved it to Majestic Park, where it operated until 1952.

“My dad, Pat Dugan, grew up across the street from the field on Whittington,” Mike Dugan said. “He told the story of how he used to mow the grass at the school and got to meet many of the legendary players of that era. He told me that one of the neatest things that happened was when Jimmie Foxx of the Philadelphia Athletics and later the Red Sox, who was his favorite player, would play catch with him in the mornings. The future Hall of Famer gave my dad a first baseman’s mitt, which he kept for years.

mow the grass at the school and got to meet many of the legendary players of that era. He told me that one of the neatest things that happened was when Jimmie Foxx of the Philadelphia Athletics and later the Red Sox, who was his favorite player, would play catch with him in the mornings. The future Hall of Famer gave my dad a first baseman’s mitt, which he kept for years.

Honus Wager read in a Hot Springs newspaper in 1909 that Hot Springs High School was trying to form a basketball team. Wagner and several of his Pirate teammates agreed to teach the boys how to play basketball. Wagner owned a sporting goods store in Pittsburgh. He had uniforms and shoes shipped from his store for the boys to wear. One of those high school players was Leo P. McLaughlin, who would later rule the city with an iron fist as mayor.

Most of the teams had moved south to Florida by the late 1920s, but the void was filled by Negro League teams. Foley also plans to pay attention to that era.

“I’m into this story,” he said Thursday. “I cannot wait to tell it. The idea is to bring the story of spring training in Hot Springs alive.”

Foley plans to reach out to the baseball clubs that once trained in Hot Springs to see if there are items in their archives that might be of interest.

“Plenty of stuff exists, but it’s going to take some digging,” he said. “It’s a little like being an archaeologist.”

The digging process has begun for Larry Foley. I can’t wait to see the final product.