Eddie Miles And How Scipio Jones High

Became Arkansas’ Most Dominant Basketball Program

The state title North Little Rock High School won on March 9, 2013, in Little Rock was a long time in coming.

Forty two years in coming, to be exact. But after firmly wiping away any worries of a late-season collapse with a 64-52 win over Fayetteville High in the state finals, the only question remaining for the 2013 7A champion Charging Wildcats is whether its 28-1 season will ultimately mark the start of a dynasty.

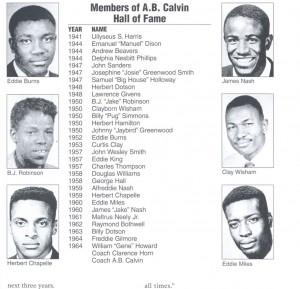

The city of North Little Rock has already produced a few superb runs in prep basketball. From 1964 through 1971, North Little Rock High won four state titles in the Arkansas Activities Association’s largest classification. And in 1948-1952, the city’s all-black Scipio A. Jones High School won four state titles in the Arkansas State Athletic Association – the organizing body for the state’s African-American prep athletes – before it joined the all-white AAA in 1967.

But the most dominant stretch of all eras belonged to the Scipio Jones teams which played from the 1955-1956 through 1958-59 seasons. These squads won four consecutive state titles, beat some of the best teams from Texas, Illinois, Tennessee and Oklahoma and annually represented Arkansas at the National Negro high school tournament in Nashville, Tenn. There, Jones finished second in 1959.

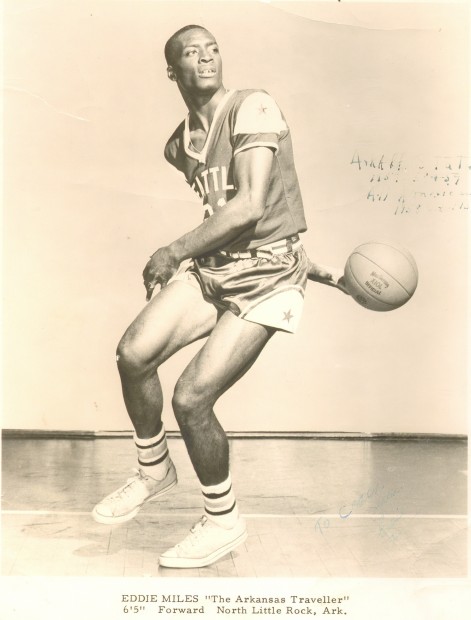

Ron Ingram, Sr., former head basketball coach at North Little Rock High, is familiar with the best players of that era and the modern one. He believes the late ‘50s Jones teams were “head and shoulders above a lot of these teams coming out” today. They shot better than today’s players, he said, and perhaps no shooter in any era of the state’s largest classification was more prolific than Jones’ do-it-all star Eddie Miles.

“He could drop 50 on you whenever he wanted,” Pine Bluff Merrill High’s Clifton Roaf told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette in 2001. “Sidney Moncrief was good, but he was no Eddie Miles.”

As a 6-4 freshman in 1955-56, Miles averaged 21 points a game and helped lead the Dragons to a 58-56 win over Pine Bluff Merrill for the state title. He accompanied junior standout Charles Thompson, a 6-3 center with an ambidextrous hook shot, in a complementary role similarly filled this season by North Little Rock High’s 6-3 shooting guard Kevaughn Allen.

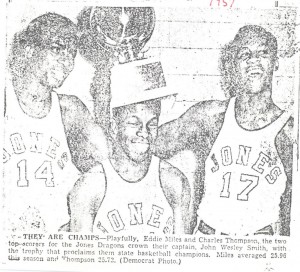

In 1956-57, Jones went 30-4 as Miles and Thompson both averaged more than 25 points a game. Other starters includedcaptain John Wesley Smith, Norman Handy and Michael Carpenter. Again, Jones beat Merrill in the finals, this time 54-52. In the national tournament, Jones beat Bluefield, W. Va. 53-43 before a 64-51 quarterfinal loss to Middleton High of Tampa Bay, Fla.

In the next two seasons, Jones didn’t lose a game to an in-state opponent. It knocked off defending negro national champion St. Elizabeth of Chicago, 40-34, at its home gym in January 1958. William McCraw, who played on the Jones varsity 1956-58, said the gym – a small, rickety structure known as “The Barn” – gave an unusual advantage to the home team.

In the next two seasons, Jones didn’t lose a game to an in-state opponent. It knocked off defending negro national champion St. Elizabeth of Chicago, 40-34, at its home gym in January 1958. William McCraw, who played on the Jones varsity 1956-58, said the gym – a small, rickety structure known as “The Barn” – gave an unusual advantage to the home team.

“The rafters hung sort of low and sometimes if you threw [the ball] too high it would hit the rafters,” McCraw said. He added while the Dragons were used to this quirk, their opponents weren’t.

Head Coach Albert Booker Calvin, who went by “A.B.,” was a far more important reason for Jones’ success. The epitome of old-school, Booker was a take-charge disciplinarian who firmly insisted on rigorous practice of the game’s fundamentals. “I used to call him Coach ABC,” McCraw said.

Eddie Miles added, “You couldn’t make Coach Calvin’s team if you couldn’t play defense.” Miles, who works as a private basketball coach and math tutor in Seattle, said “the main thing that made us so effective was that we played defense.” Miles, age 72, has made Washington his longtime home after a successful career at Seattle University* where he earned All-America honors. He later played nine seasons in the NBA, earning All-Star honors in 1966 with Detroit.

As a junior in high school, Miles kept winning with new running mates – including McCraw (an all-state selection as a senior), playmaker James Nash and 6-3 big man Eugene Ross. Miles averaged more than 30 points that season. Jones capped it by beating Miller High of Helena 45-32 in the state tournament at what’s now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff before beating Monticello 90-55 in the finals. In the nationals, the Dragons edged a team from Suffolk, Va. before losing to Pearl High of Nashville, Tenn., 82-68, in the quarterfinals.

Senior year was more of the same; Jones beat every in-state opponent while Miles topped more than 32 points a game. He had one of his worst games in the state finals against Central of Lake Village but Nash stepped up to score 32 points for an 82-79 overtime win.

Miles came back with a vengeance in the national tournament where he averaged 41.75 points as Jones roared through opening rounds, past teams from Scotlandville, La., Atlanta, Ga. and Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Nashville’s Pearl High, though, again proved to be a thorn in the side during the finals. This time Jones lost 76-72 in overtime; Miles and Nash were afterward named All-Americans.

Miles and McCraw stay in touch with other Jones alumni, but don’t feel any special connection to North Little Rock High, which absorbed Jones’ students after Jones High closed in 1970. Still, they enjoy hearing news about the Charging Wildcats’ success, even if they can’t make it to the games.

which absorbed Jones’ students after Jones High closed in 1970. Still, they enjoy hearing news about the Charging Wildcats’ success, even if they can’t make it to the games.

They well know, after all, this most recent championship by a North Little Rock program is only part of a legacy reaching back decades. “I hope they have many more,” Miles said. “They probably will.”

The above article originally published in The North Little Rock Times

*Why Miles Attended Seattle, Not Arkansas

The short answer is simple: the Southwestern Conference’s color barrier wasn’t yet ready to be broken, and wouldn’t be until 1965.

The long answer is more complicated.

Miles grew up a Razorbacks fan, like almost everybody around him. He faithfully listened to Hogs football and basketball games on the radio, and especially liked Bruce Fullerton, a highly decorated prep fullback at Little Rock Central who graduated in 1958 before briefly playing for the Hogs.

“I was a Bruce Fullerton fan,” Miles said. “I never thought about I was black and he was white.

“Players, when they play, they usually don’t care what color you are. They want to play, they want to compete.”

And so, as a teen, it didn’t matter to him that the UA’s football and basketball teams continued to be all-white while Northern programs regularly fielded integrated teams.

“You really don’t notice that kind of stuff going on… You never said ‘Well, we’re [seen as] second-class citizens or whatever, and I’m not gonna pull for them.’ You just didn’t think about that. And I think athletics has done more to bring races together than anything else.”

In the late 1950s, Arkansas head basketball coach Glen Rose was eager to reestablish the Hogs as a Southwest Conference power, and he knew Miles could help him do it. But no official athletic scholarship was offered.

Instead, Rose told Miles’ high school coach, A.B. Calvin, that Miles – who had more than 50 offers from various programs – would initially receive an academic scholarship and be a walk-on.

Once Miles made the team, as he almost certainly would have, Rose said he’d get an athletic scholarship.

“But Coach Calvin said ‘No,’” Miles recalled. “Because there were teams like Mississippi and Louisiana and other sorts of schools who had laws on the books that their team wasn’t supposed to play against other integrated teams so he said in a lot of games I wouldn’t be able to play.

“But I did want to go,” Miles said. “I wanted to go. But [Coach Calvin] said ‘No.’

“I’d end up not being able to play in a lot of games.”

One place Calvin believed Miles would get plenty playing time was what’s now Tennessee State University, the historically black college in Nashville, Tenn. Without discussing the matter with Miles, Calvin arranged with the head coach of TSU for Miles to play there. Miles, though, had a different idea.

One place Calvin believed Miles would get plenty playing time was what’s now Tennessee State University, the historically black college in Nashville, Tenn. Without discussing the matter with Miles, Calvin arranged with the head coach of TSU for Miles to play there. Miles, though, had a different idea.

During the national high school tournament he met a recruiter for Seattle University, where his favorite player Elgin Baylor had starred. It just so happened this recruiter was also the cousin of Baylor, who’d went on to a Hall of Fame career with the Los Angeles Lakers.

It didn’t take long to sway Miles.

“Elgin gave me a call, and I was sold,” he said. “Seattle U, here I come. Goodbye, Tennessee State.”

It’s fun to imagine how good the Hogs would have been with Miles teaming up with the likes of Jerry Carlton and Tommy Boyer in the early 1960s. Surely, the long dry spell of 1949-1977 (in which Arkansas made only one NCAA Tournament appearance) would have been less arid.

But it appears unlikely Miles would have been able to play for Arkansas even if his high school coach had been on board. Around 1959, university officials told Glen Rose “the school was not ready to break its color ban,” according to a United Press International article in Jan. 1966.

The article continues:

“Rose said he understood Miles, who was then 6’4” tall, wanted to come to Fayetteville but was forced by the university’s administrative stand to go elsewhere. He later starred at Seattle.

The university now is under a court order not to discriminate in several fields, including athletics, and a Negro – 6-1 Louis Bryant of Fayetteville – is playing on the freshman squad.

He is the first member of his race to compete athletically at Arkansas.” [n.b. Darrell Brown, who walked on to Arkansas’ football team as a freshman running back in summer 1965, may actually be the first.]

While Miles never did play for the Arkansas program he grew up rooting for, the great success he enjoyed at Seattle University might have helped soften UA administrators’ stance, ultimately opening the door for the state’s next generation of African-American prep stars.

In the early 1970s, Almer Lee became the first African-American to earn a letter on the Hogs’ basketball team. With the likes of Sidney Moncrief and Ron Brewer just around the corner, the program would never again be the same.