Summer has officially arrived, and no group was happier to see the spring of 2013 end than residents of the Oklahoma City area. The region was hit by major tornadoes this spring that took lives and did tens of millions of dollars in damage. Among those who lost homes was a former Arkansan named Bennie Fuller.

Those of us who grew up in this state and are of a certain age need no introduction to Fuller.

He was, quite simply, one of the greatest high school basketball players in Arkansas history. The fact he’s deaf just makes the story more intriguing.

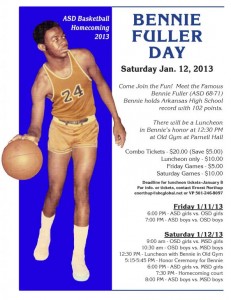

Back in January, the Arkansas School for the Deaf in Little Rock named its basketball court for Fuller, who was in attendance at the ceremony along with his wife, Emma. Also there was Little Rock’s Emogene Nutt. Her late husband, Houston Nutt Sr., was Fuller’s coach. Emogene was the mother hen who treated all of the athletes as if they were her sons. She, of course, has four sons – Houston, Dickey, Danny and Dennis – who went on to careers as college coaches.

Emogene Nutt refers to Fuller as the “Wilt Chamberlain of the deaf.” She devoted more than three decades of her life to the school and considers Fuller “a once-in-a-lifetime athlete.” Houston Sr., who died in 2005, no doubt would have agreed.

For those who wish to help the Fuller family, an account has been set up at First Security Bank. Checks can be made out to the Bennie Fuller Donation Fund and left at any First Security location across the state.

Bennie Fuller Day flier from earlier this year.

Fuller is the all-time leading scorer in Arkansas boys high school basketball history and fourth on the national list. He scored 4,896 points at the School for the Deaf from 1968-71.

All of those ahead of him are from Louisiana. Greg Procell of Noble Ebarb scored 6,702 points from 1967-70, Bruce Williams of Florien scored 5,367 points from 1977-80, and Jackie Moreland of Minden scored 5,030 points from 1953-56.

Procell, who is Choctaw-Apache, played at what later became a designated Indian school on the banks of Toledo Bend Reservoir about 70 miles south of Shreveport. There were no limits on the number of games that could be played in that era, and Ebarb played 68 games during Procell’s senior season.

In Arkansas, no one comes close to Fuller for career points. Jim Bryan of Valley Springs is second with 2,792 points from 1955-58, and Allan Pruett of Rector is third with 2,018 points from 1963-66.

Fuller is third nationally on the per-game scoring average list (50.9 points per game during the 1970-71 season) behind Bobby Joe Douglas of Louisiana (who averaged 54 points per game at Marion High School in 1979-80) and Ervin Stepp of Kentucky (who averaged 53.7 points per game at Phelps High School in 1979-80).

In 1971, Fuller scored 102 points in a game against Leola that was played at Arkadelphia.

“I didn’t know I had 22 points in the first quarter and 44 points at halftime,” Fuller said in an interview several years ago through a sign language intepreter. “I wasn’t counting. We were just playing. At the end, I had no idea I scored 38 points in the fourth quarter. It was like a machine gun, one after another. It was just nuts. I had some big nights before. If I had to guess that night, I would have thought around 70. But they showed me the scorebook. It was incredible.”

This was, mind you, long before the three-point shot. Here’s how it broke down that night in Arkadelphia in each of the eight-minute quarters:

- First quarter: Nine field goals and four of five from the free-throw line for 22 points.

- Second quarter: Seven field goals and eight of 11 from the free-throw line for 22 points.

- Third quarter: 10 field goals for 20 points.

- Fourth quarter: 15 field goals and eight of eight from the free-throw line for 38 points.

Fuller had grown up near Hensley, where he learned to shoot a basketball into a hoop made from a bicycle wheel. By his senior season in high school, college coaches were filling the stands at the School for the Deaf to watch the Class B team play. After campus visits to Arkansas, UTEP and Memphis, Fuller chose to attend Pensacola Junior College in the Florida Panhandle.

Why Pensacola Junior College?

Bob Heist explained in a story for the Pensacola News Journal: “Jim Atkinson, an assistant on the coaching staff at the time, accepted the head job at PJC on an interim basis when Paul Norvell unexpectedly left during the spring recruiting period. The Pirates’ program wasn’t competitive … so the new coach returned to some old roots for talent. A native of Fordyce, Atkinson shared the same hometown as the state’s first family of the deaf – the Nutts. All the children were born with either serious hearing or speech impediments, including Houston Nutt Sr., the only person to play for basketball coaching greats Adolph Rupp at Kentucky and Henry Iba at Oklahoma A&M.

“Nutt, whose speech was impaired from birth, was the coach and athletic director at the Arkansas School for the Deaf. His brother, Clyde, was a sensational athlete who led the 1957 U.S. deaf basketball team to the world championship in Milan, Italy. Clyde’s son, Donnie, was full hearing and an accomplished player at a Little Rock public school, and he understood sign language. Why did Fuller choose PJC? The school offered a vocational trade course in technical typesetting he was interested in, plus Atkinson offered a scholarship to Donnie Nutt. No other school could accommodate Fuller with a personal interpreter.”

Atkinson told Heist: “I had heard of Bennie and what he had done like everyone else, plus I knew Houston was the head coach and athletic director. To be honest, I was trying to find someone to tie our next season to, that one player who would make it interesting for fans. To me, that had to be Bennie. Then I learned about Donnie. I didn’t know how to do sign language, and he was also a very good player. I had a spot, so we kind of got two birds with one stone.”

Fuller averaged more than 30 points per game and Donnie Nutt averaged more than 20 points per game in 1971-72 even though PJC only went 7-18. Atkinson was replaced at the end of the season by a junior college coach from Missouri named Rich Daly. Daly brought in a number of highly touted recruits, and Fuller and Nutt found their roles reduced as the Pirates went 26-4. Daly would later go on to serve as a longtime assistant for Norm Stewart at the University of Missouri.

Fuller received an associate’s degree after two years. He moved to the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff but was only a role player for the Golden Lions. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from UAPB, he taught at the School for the Deaf for a time before beginning a long career in Oklahoma with the U.S. Postal Service. He and his wife have four children, all of whom can hear.

Fuller’s 102 points on Jan. 19, 1971, against Leola are the most points ever scored by a deaf high school player in a certified varsity game. Fuller is also believed to be the first deaf player to receive a college basketball scholarship at a hearing institution.

“In the world of the deaf, Bennie Fuller’s name resonates like a midnight lightning strike,” Heist wrote. “He is the legend for the hearing- and speech-impaired.”

Or as Emogene Nutt puts it, there was no one like Bennie Fuller in the deaf community before and has been no one like him since.

Now, Arkansans are being called on to lend a hand to this native son.